Melody, a 32-year-old patient (G14 P8) at 33+5 weeks gestation has been transferred from a peripheral hospital for antepartum haemorrhage. She has a known major placenta praevia this pregnancy. She last had a small bleed with clots 2 hours ago. Otherwise she feels well and FHR and CTG are normal.

Past Medical History:

Heavy smoker (~ 20cigs/day)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

OSA (not on CPAP)

Asthma

Obstetric History:

3 NVD term pregnancies

5 previous LSCS under neuraxial anaesthesia

- 2 preterm (32 weeks and 35 weeks)

Medications:

Protophane 88 units nocte

Novorapid 12 units TDS

Allergies:

nil

Observations:

HR 94 BP 128/70 SpO2 95% (RA) RR 20 Temp 36.7 degrees Celsius

Weight: 96kg

Height: 115cm

BMI: 42 kg/m2

Obstetrics are concerned she also has placenta accreta syndrome and has recommended a MRI for planning delivery but Melody frequent leaves the Birthing Unit to smoke and misses her scan.

Candidate has 2 minutes reading time to plan their initial response to the first question below

Click each question to reveal a suggested answer

OPENING QUESTION

1. Briefly outline what placenta praevia and placenta accreta syndrome (PAS) are and the broad perioperative implications of these conditions

They are uncommon conditions of abnormal placenta implantation.

Placenta Praevia

Abnormal placental tissue development, overlying or in close proximity to the internal cervical os, in advance of the presenting fetus.

Broadly classified as minor or major depending on its distance from the cervical os

- Major: lying directly over the internal cervical os

- Minor: Placental edge is less than 20 mm from the internal os after 16 weeks gestation on US ("low-lying")

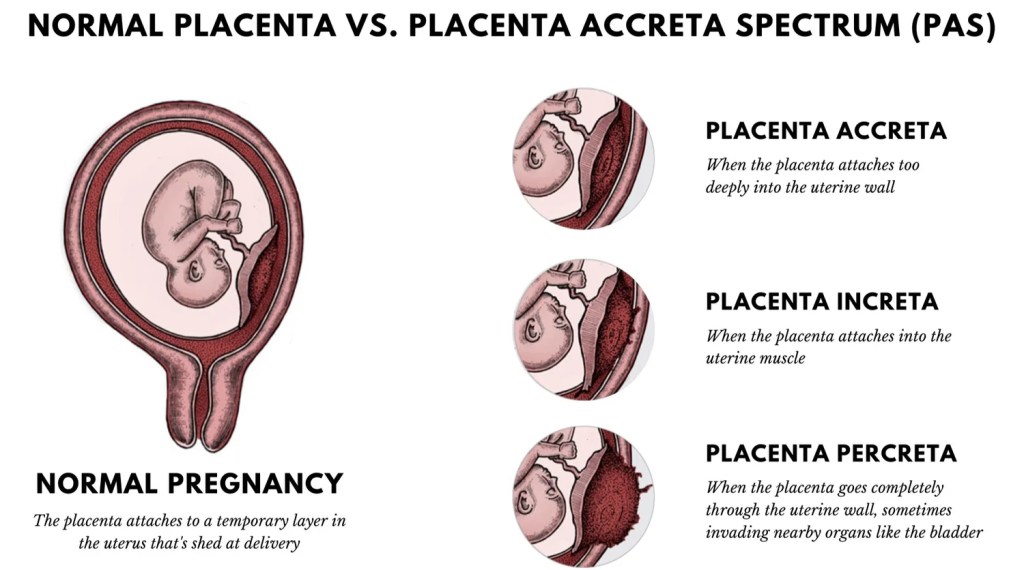

Placenta Accreta Syndrome (PAS)

A term used to include both the abnormally adherent and invasive forms of accreta placentation

Accreta or adherent: villi adhere superficially to the myometrium without interposing the decidua

Increta: villi penetrate deeply into the uterine myometrium through to the serosa

Percreta: villi perforate through the entire uterine wall and may invade the surrounding pelvic organs, such as the bladder.

Implications

Vaginal delivery is contraindicated in major placenta praevia and PAS. For both conditions there is a significantly increased risk of APH (RR 2.6), PPH (RR 5.4), blood transfusion (RR 17.8), hysterectomy (RR 234.9) and ICU admission (RR19.1).

An MDT approach is required with the obstetric team, with least an MFM specialist, anaesthetist, haematologist, neonatologist, intensivist, and potentially a Urologist or General Surgeon.

Patient Blood Management protocols, PPH Protocols including a clear stepwise escalation plan for severe PPH are the foundational principles of management.

Regarding mode of anaesthesia: primary neuraxial technique to initiate Caesarean delivery is shown to be safe however, surgery will be prolonged and the patient will likely require a GA at some point. Also in the event of acute APH, there will highly unlikely be enough time for even a rapid spinal block in that specific emergent setting.

PROGRESS QUESTIONS

2. Describe the key risk factors in this patient that increase her risk of developing placenta praevia and PAS?

This patient presents with multiple major risk factors for severe PAS and subsequent massive PPH:

Critical Risk Factors for PAS/PPH:

1. Placenta praevia overlying a previous Caesarean scar: This is the most common and important risk factor for PAS. Her risk of abnormally invasive placenta is dramatically increased given the combination of current placenta praevia and history of prior LSCS. With 5 previous LSCS, her risk of PAS is likely greater than 60%.

2. Grand Multiparity (G14 P8): Multiparity is an established risk factor for PAS.

3. Outline what other further assessment you’ll undertake regarding her overall perioperative risk?

Melody requires consultation as early as possible. In addition to the standard obstetric anaesthetic assessment via history, exam and investigations, I would focus on her airway, the severity of her known co-morbidities of heavy smoking, diabetes, OSA and asthma and any secondary complications related to these, particularly cardio-respiratory disease.

I would screen for any antenatal medical conditions that could compound her bleeding risk such as pre-eclampsia and thrombocytopaenia.

I would review her previous anaesthetic charts given her extensive Caesarean delivery and note any problems related to neuraxial anaesthesia.

History

Asthma & Smoking:

- chronic cough particular nocturnal, frequency of chest infections, wheeze, reduced exercise tolerance, inhaler therapies and any increased PRN use, particularly in last 4 weeks.

- I'd advise her to stop smoking, and try nicotine substitution therapy. It will also help her stay in the Birth Unit

OSA:

- clarify if this is a diagnosis on polysomnography and if not do a STOPBANG screen.

Type 2 diabetes:

- degree of control?

- What are her random, pre- and post-meal BSLs?

- Has there been an escalation in insulin dosing in the last few weeks?

- Any hypoglycaemic events, gastroparesis related reflux symptoms?

Examination

Airway:

- assess of signs of difficult intubation and BMV given her BMI 42 and OSA history. Dentition may be poor given heavy smoking history

CVS/RESP:

- Ascultate for wheeze and murmus. Look for signs of heart failure associated with severe untreated OSA

Other:

- Spine examination for ease of possible neuraxial technique

Investigations

FBC

UEC

Coags + Fib

ECG

Uterine US - determine if placenta accreta is present and its severity

4. Melody reports she has a daily chronic dry cough and typically gets bronchitis once a year that requires a course of antibiotics from the GP. She has noticed a decline in exercise tolerance but puts it down to 3rd trimester pregnancy. She has not had any wheezing and does not use inhalers. Her glycaemic control is good with the current insulin regimen. Her GP sent her for a sleep study 12 months ago but she never got told the result. She denies any hypertension during pregnancy or any other antenatal issues apart from PV bleeding in the last 3 weeks. Neuraxial anaesthesia in previous deliveries were all straightforward. She’s never had general anaesthesia before.

Interpret these investigations:

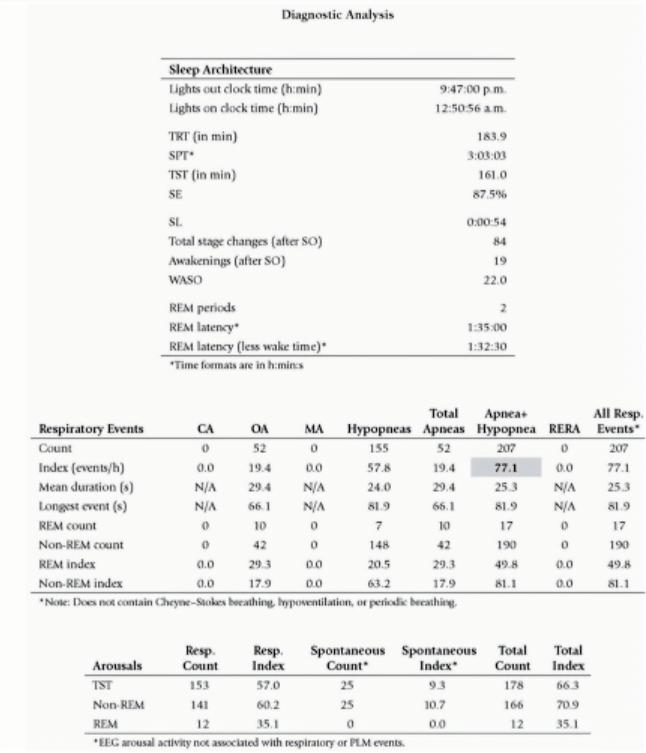

This requires the candidate to demonstrate basic understanding of the key results of PSG to diagnose OSA including relevant terminology.

TST: total sleep time

Apnoea: complete cessation of airflow for >10 seconds

Hyponoea: >50% airflow for >10 seconds

AHI: Apnoea Hyponoea Index - total of both events / hour

RERA: Respiratory Effort Related Arousal - a temporary awakening from sleep detected by EEG that occurs ≥10 seconds of partial obstruction to airflow, but not severe enough to be classified as apnoea or hypopnoea

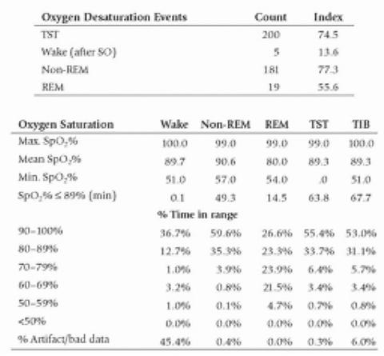

Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI) - The average number of desaturation episodes per hour with ↓mean SpO2 ≥4% lasting for at least 10sec. ODI is directly proportional to AHI

Overall this PSG is diagnostic for severe OSA

Over a 3h sleep, this patient had an AHI of 77 with the mean duration of apnoeas / hypopnoeas between 24 - 29 seconds. The longest event was almost 1.5min.

There were 200 desaturation events with mean desat down to 89% but the lowest during both REM and non-REM sleep was in the 50s. This gave an ODI of 74 which correlates well with the AHI result.

She would significantly benefit from CPAP therapy.

5. How does this impact your assessment of her perioperative risk?

The risk of untreated severe OSA is significant. These patients are twice as likely to have a 30-day risk of composite MACE complications (HR 2.23, POSA Study).

In the setting of a Caesarean delivery, particularly under GA, this is specifically concerning for Melody.

It further supports a plan for invasive cardiac monitoring and at minimal HDU monitoring post-operatively.

6a. The remainder of Melody’s examination and investigations are unremarkable. Her Hb 120, Platelets 229, Cr 44 and eGFR > 90. The following day she returns hurriedly to the birth unit after having a smoke, anxious about feeling severe perineal and suprapubic pain and a large gush while outside. The obstetric registrar examines her and estimates 200mL fresh blood loss. There is no active bleeding. FHR is 150. A Cat 1 emergency LSCS is booked. Outline your anaesthetic plan?

The acute bleed combined with new pain raises suspicion of a placental abruption

Expect candidate to outline broadly the pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative plan

Part of the urgent pre-op planning is to ensure all other auxiliary relevant team members and specialities are immediately alerted and readily available. This includes:

1. HDU/ICU bed for the mother post-op

2. NICU team to receive baby for immediate resuscitation, given prematurity and high risk of intrapartum distress

3. Cell saver machine and operator

4. Blood bank - pre-warn regarding high chance of MTP required +/- RiaSTAP

Intra-Op Plan

Goals:

- Be prepared for prolonged Caesarean section with high probability for hysterectomy

- Be prepared for massive blood loss

- Defend the patient from aspiration

- Defend the patient from awareness

- Optimise post-op pain with multi-modal approach given LSCS have a high risk of chronic post-surgical pain - likely worsened without ITM

Anaesthesia:

Relaxant GA with RSI

Monitoring:

Standard

+ arterial line

+ BIS (or equivalent)

+ temperature probe

Access:

1 x Rapid infusion catheter (RIC)

2 x large bore IVC

Drugs:

- TXA

- Uterotonics

- Metaraminol (or any other vasopressor)

Extra

- Valid G&H + Blood in room - at least PRBC x 2

- Cell saver

Post-Op Plan

Extubate

HDU/ICU

6b. (This question is only if candidate plans for neuraxial approach first. Click for the expected response. Otherwise skip to Question 6c.)

Collaborate with Obstetrics if there is enough time for spinal / CSE

(A de novo epidural is obviously not appropriate - too slow, risk for patchy block)

Expectations of candidate:

- give type of needle, level of block, specific doses for all drugs used in the spinal block

- acknowledge that GA would eventually be likely and outline the key factors that would trigger conversion to GA or the planned timing to initiate this

- state benefits of starting with neuraxial anaesthesia first as opposed to a GA

- monitoring, access, drugs and extra resources would be the same as GA with exception to BIS and temperature probe

e.g.

Sprotte 25G, L3/4 intervertebral space. Bupivacaine 0.5% (hyperbaric) 2.4mL, Fentanyl 20mcg, IT Morphine 100mcg

Benefits:

- facilitates mother-baby bonding

- salvages the unique potentially once in a lifetime experience of birth

- superior post-op pain for Caesarean section & abdominal hysterectomy

- if surgeon is quick, could potentially avoid GA altogether and additional anaesthetic agents affecting uterine tone e.g. sevoflurane

Move on to Question 6d.

6c. Describe your induction?

RSI:

Patient draped, surgeon scrubbed ready for KTS.

Following pre-oxygenation in a ramped position, aiming for ETO2 of 80 - 90%, I would bolus Alfentanil 1mg, Propofol 170mg, Rocuronium 1.2mg/kg

Intubate with ETT#7 using a videolaryngoscope and confirm placement with ETCO2

6d. (This question is for candidates who answered Question 6b). The neuraxial block is effective but the dissection is slow. The baby is delivered after 1 hour. Despite the cautious approach, the bleeding is difficult to control. The obstetrician commits to a hysterectomy and requests you convert to a GA. Describe your induction?

Managing patient and partner expectations:

Patient's partner would likely be in the room to start with in this scenario. Expect candidate to make some comment about how this is managed if mid-case conversion is required.

e.g. explain what is happening. Assuming a spare midwife/nurse is available to tend to the partner, the option to stay or go during the induction of GA should be offered.

RSI:

Recognise this is a high risk induction for a haemodynamically unstable patient.

While pre-oxygenating in a ramped position, aiming for ETO2 of 80 - 90%, I would bolus a 1L of warm CSL followed by Alfentanil 750mcg, Propofol 120mg, Rocuronium 1.2mg/kg and 0.5mg of metaraminol (candidate must have a dose reduction in their induction of a haemorrhaging patient)

Intubate with ETT#7 using a videolaryngoscope and confirm placement with ETCO2

7. Outline the issues you’d consider to favour a GA over neuraxial as the primary mode of anaesthesia

Neuraxial Anaesthesia (NA) has good evidence for safety in PAS in scheduled non-emergent cases, and other benefits including early mother-baby bonding and good post-operative analgesia. However, for this specific patient, combining the balance of maternal risk factors, urgency, and expected surgical complexity, GA is also a justified choice.

1. Urgency and Hemodynamic Instability Risk

Nancy has had an acute APH and suspected abruption. There is a high risk she could suddenly have another bleeding episode while OT is prepared. In the event of rapid, uncontrolled hemorrhage, securing the airway early under controlled conditions is paramount. The sudden sympathectomy induced by NA may hinder compensatory physiology during active hemorrhage.

2. Complex Surgery and Anticipated Prolonged Duration

Caesarean section for high-grade PAS is a complex, long procedure. The surgery may require ureteric stenting for extra-uterine involvement and a total hysterectomy. Neuraxial block may be inadequate for the duration or the extent of surgical exposure, leading to unplanned conversion to GA in the middle of massive bleeding. Elective conversion is still necessary in up to 45% of cases requiring hysterectomy.

3. Patient-Specific Risks (Airway & Neurological)

Difficult Airway: The patient has a high BMI (42) and known OSA. GA allows the airway to be secured in a controlled manner before the onset of massive transfusion, which can cause severe airway edema and further compromise intubation efforts.

CHALLENGE QUESTIONS

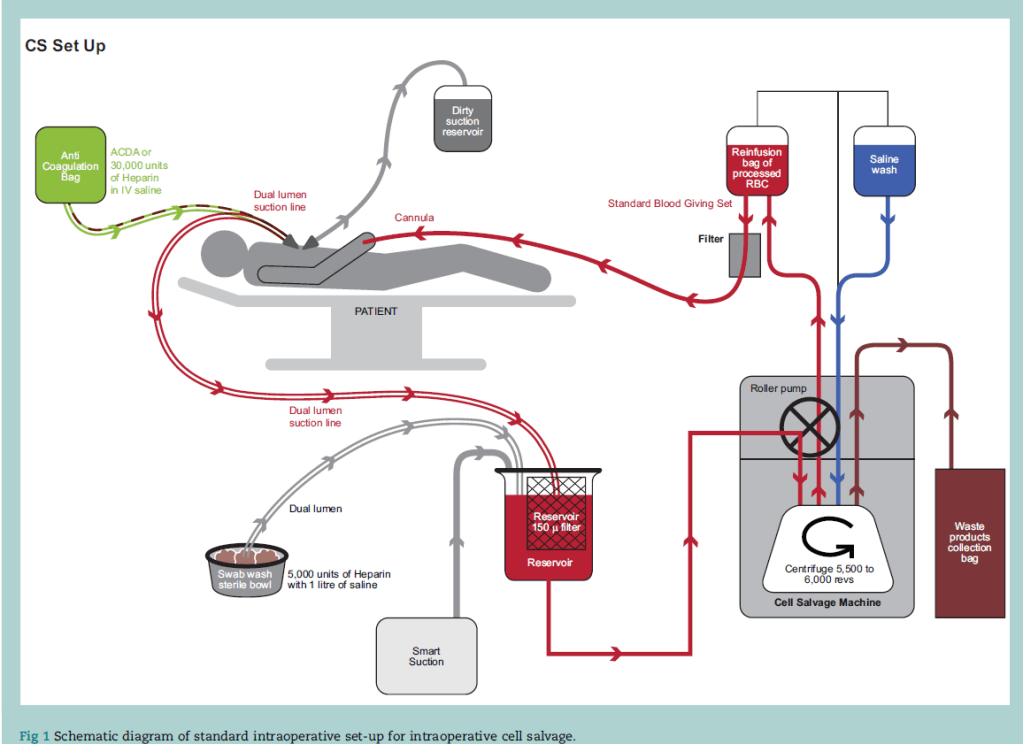

8. Melody is induced and intubated without difficulty. After delivering the baby, massive haemorrhage ensues as the obstetrician had to dissect through the placenta and it is difficult to extract its entirety from the uterus. The cell saver has been activated. Briefly describe how cell salvage works?

Intraoperative cell salvage (ICS) is the method of harvesting red cells during surgery, and processing them for reuse as an autologous red cell transfusion during or immediately after surgery.

6 Steps

1. Suction - low pressure 100 - 150mmHg (decr haemolysis), wide-bore, double lumen. Anticoagulant is delivered to suction line via internal stubing

2. Filtration (150 microns) - microaggregates, clots, debris

3. Separation - centrifugation with saline wash separates RBCs from the waste

4. Disposal - waste products collected and removed (WBC, plasma, fat, free Hb)

5. Salvage - RBCs washed in IV 0.9% N/S and collected

6. Re-infusion with a filter - within 6h - RBCs start to degrade after this -> reduced deformability and function

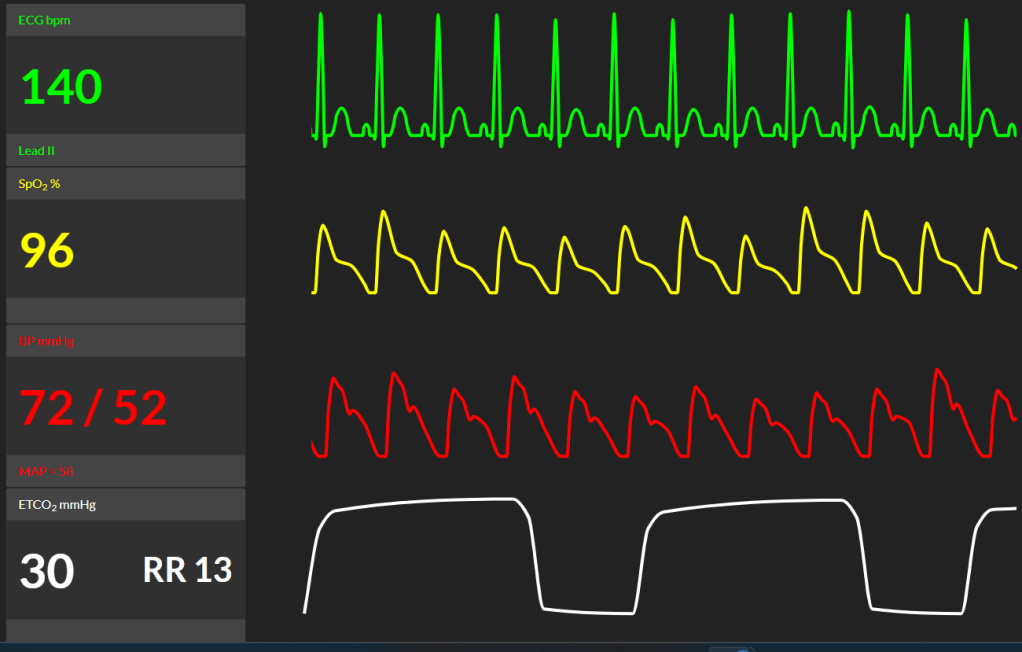

9. The EBL rapidly hits 2000 mL. The vital signs on your monitor are (click to reveal):

How do you approach this situation?

Expect: state the diagnosis and very briefly demonstrate that other differentials are not forgotten. If management steps are omitted, prompt candidate.

The patient is in severe hypovolemic shock

Less likely but pertinent differentials include anaphylaxis and embolic phenomena including air and amniotic fluid embolism.

I would aggressively resuscitate with a goal-directed approach to stop the cycle of hemorrhage, coagulopathy, and acidosis.

Immediate Priorities:

1. Surgical Control: Demand immediate confirmation from the surgeon regarding the source and methods for temporary control (e.g., clamping, packing, proceeding to definitive hysterectomy).

2. MTP Implementation: Ensure MTP is fully activated and the first pack (PRBC, FFP, Platelets) is rapidly infusing via the rapid infuser device through the largest bore lines.

3. Hemodynamic Support: Utilize the arterial line for continuous monitoring. Vasopressor support (e.g., Phenylephrine / metaraminol / Noradrenaline) should be instituted early to maintain mean arterial pressure and perfusion.

4. Baseline coagulation and acid/base status: ABGs and ROTEM.

Transfusion Strategy and Ratios:

While there is no consensus on the ideal ratio for PAS, expert consensus suggests ratios of PRBC to FFP between 1 : 1 and 2 : 1 during massive transfusion.

• Initial Resuscitation: Start with a 1:1 ratio of PRBCs and FFP (e.g., 4 units PRBC: 4 units FFP) from the MTP pack.

• Fibrinogen Replacement: The prompt replacement of fibrinogen is critical as it falls earlier than other clotting factors in PPH. I would anticipate hypofibrinogenemia and initiate early, targeted replacement.

Key Adjuncts: Ensure the initial dose of Tranexamic Acid (TXA) 1g IV is accounted for, and consider a repeat dose if bleeding persists.

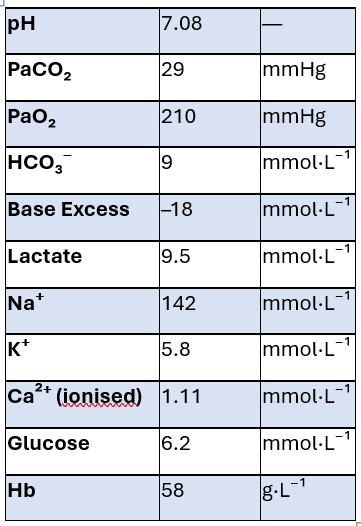

10. The ABG has returned. Please interpret and describe any changes in management

Severe metabolic acidosis from lactic acidosis and poor perfusion secondary to massive acute haemorrhage.

Low HCO₃⁻ and large negative base excess indicate uncompensated metabolic component.

Mild hyperkalaemia due to acidosis and cell breakdown.

Very low Hb consistent with severe haemorrhagic shock.

I would continue with MTP and warn blood bank that a 2nd MTP maybe required.

Gather extra personnel to help check and prep blood products. Bolus via a fluid warmer.

11. What is ROTEM? What information does it provide?

Rotational Thromboelastometry - a viscoelastic haemostatic assay (VHA) test. It is a point of care test that provides dynamic, real-time information about:

- clot formation,

- clot strength,

- and clot lysis

Offering a faster and more accurate assessment of coagulation kinetics during active hemorrhage compared to standard coagulation tests

Despite the theorectical advantages of using ROTEM in managing critical bleeding, there still lacks strong evidence to show that it reliably has an impact on mortality and reduced transfusions, including the obstetric population.

However, may still be useful in goal-directed resuscitation on case-by-case basis and detect non-surgical related bleeding which may need treatment with specific blood products / haemostatic agents.

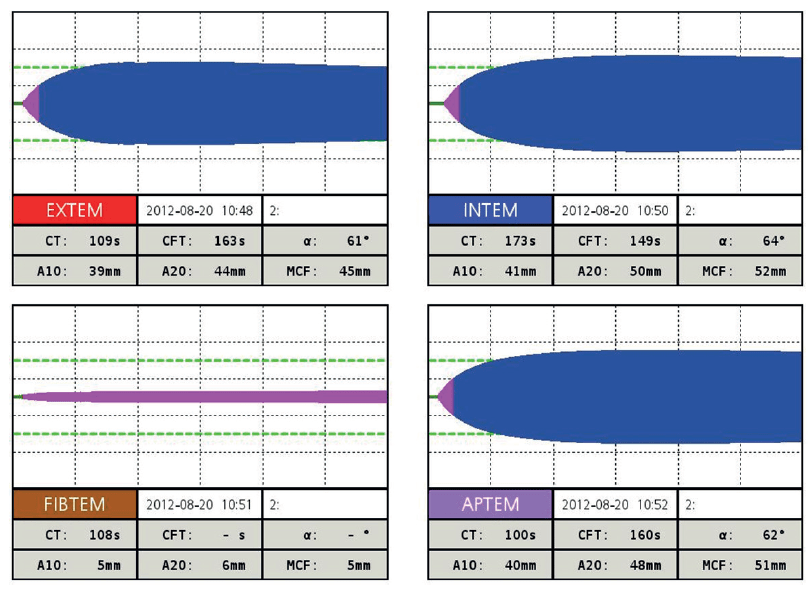

12. The ROTEM taken 20 minutes ago have some results available. (There was a computer glitch and a sample had to be re-run). Interpret and describe any follow-up action.

The candidate should demonstrate a systematic way of working through the results

EXTEM:

Prolonged CT and CFT, low MCF → severe coagulopathy and poor clot strength

→ clotting factors low

→ but no hyperfibrinolysis

FIBTEM:

A10 = 5mm

Extremely low MCF → critical hypofibrinogenaemia.

APTEM:

Similar to EXTEM → no major fibrinolysis (rules out hyperfibrinolysis).

This is in keeping with predicted obstetric haemorrhage related coagulopathy.

I would prioritise replacing fibrinogen with Fibrinogen Concentrate or alternatively cyroprecipitate, and then repeat the ROTEM and ABG.

13. Over the phone, the blood bank confirms they have RiaSTAP (Fibrinogen concentrate) available and cyroprecipitate as well . [If not already volunteered in previous response] – How does the evidence compare between fibrinogen concetrate and cryoprecipitate? Which product will you use and how do you dose it?

There is insufficient evidence to show RiaSTAP is superior to cryopreciptate in major trauma haemorrhage in terms of:

- mortality

- transfusion requirements

In obstetric PPH population, small studies are suggestive that FC does reduce

- transfusion requirements

- risk of TACO

- but makes no difference if given prophylactically at the time of PPH without a known fibrinogen level or if FIBTEM >/= 12mm

However, there is growing evidence that it is:

- faster to administer (which is important when managing critical bleeding)

- can increase FIBTEM A5 and mean fibrinogen levels to a greater extent than cryo (which can be a clinically significant difference if it changes direction of management according to thresholds in algorithms)

- may reduce risk of fluid overload c.f. traditional cryo

- historically more expensive but studies comparing FC and cryo in cardiac surgery have shown similar cost-effectiveness

Additional logistical benefits:

- increased viral safety profile

- standardised concentration of fibrinogen c.f. variable levels in cryo bags

- stored at room temperature in powder form -> facilitate immediate access and administration

- no blood incompatibility issues / risks

Cryo

1 unit per 5-10 kg of body weight should increase fibrinogen level by 0.5-1.0 g/L

• Typical adult dose is 8 - 10 units

Fibrinogen Concentrate

70mg/kg (expect serum Fib increase by 1.2g/L)

Targeted dosing: (Target Fib - Actual Fib) ÷ 0.017 = dose in mg/kg

Reconstitute in 50mL of water. Max rate 300mL/h

Treatment Targets

FIBTEM >/= 12mm

Fibrinogen >/= 2

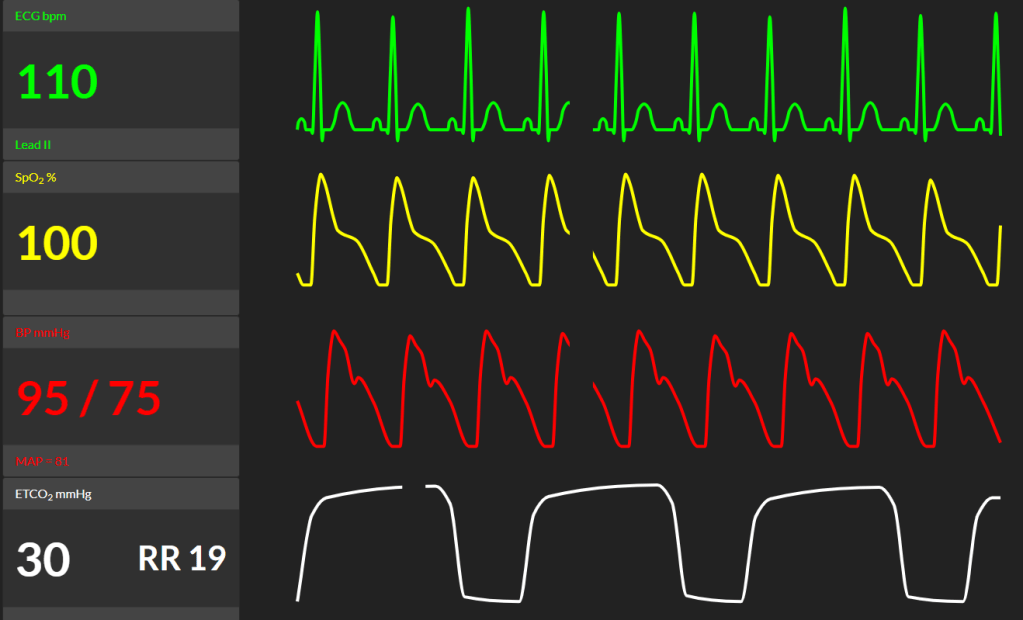

14. RiaSTAP / Cryo (whichever was chosen) is being administered along with the rest of the MTP. The obstetrician successfully completes a hysterectomy to control the bleeding. In the fray, there’s been some urological damage. The urologist has scrubbed in to repair the bladder and stent the ureters. Here are her new vital signs (click here to reveal). Outline the remainder of your management plan for this patient?

Review ABCDE starting with C - Critical Bleeding

- Reconfirm surgical haemostatic control

- Repeat ABG and ROTEM to guide next steps

- Oxytocin infusion – consider converting to concetrated low volume infusion give risk of fluid overload following MTP

- Review ventilation settings and wean down FiO2, and bronchial toileting with y-catheter suction – high risk of retain sputum in heavy smoker

- Check BSL (patient is diabetic)

- Monitor temperature and keep warm, aiming at least > 35 degrees Celsius

- Flag with ICU so they can prepare to receive patient

- Decision to extubate will be dependent on patient’s overall stability – haemodynamics, acid-base status, coagulopathy

AFTERMATH

15. The surgeon ended up doing a large classical incision to deliver the neonate and manage the bleeding. He is worried Melody will have a lot of pain after this surgery. What is your post-op pain management plan?

Expect candidate to include regional analgesic options in their response and daily follow-up with an acute pain team. Whichever block is mentioned, a follow-up question will be 'how do you perform this block'

Multi-modal strategy and also taking into Melody's unique factors including:

- breastfeeding requirements in the near future

- potential renal impairment and reduced drug elimination due to ureteric and bladder injury

- given massive bleeding, withhold regular NSAIDs until coagulation and FBC are stable

Regional block +/- catheters while under GA prior to ICU transfer:

- Bilateral TAP block or

- Bilateral QLB or

- Bilateral ESP

Regular paracetamol

Ketamine infusion for 24 - 48h

Fentanyl infusion while intubated and transition to PCA when extubated depending on severity of pain

- with plan to transition to oral opioids when pain control stable and tolerating food/drink.

16. (If not volunteered in previous response). Describe how you would perform this regional block?

Follow ANZCA Guidelines for major regional anaesthesia

Clean no touch technique

Skin prep with 2%chorhex + 70% alcohol

USG

e.g. For TAP:

Obtain image of 3 muscle layers of lateral abdominal wall - external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis and using an in-plane approach infiltrate 20 - 30mL of LA (e.g. ropivacaine 0.5%) deep to the fascia between internal oblique and TA - observing for a growing ellipse of fluid splitting the 2 muscles apart.

Ensure the dose of LA is within the systemic toxic limits

END OF VIVA

Sources

Tooze et al. Anaesthesia for Patients With Abnormal Placentation. 5 July 2023. ATOTW 500, WFSA. https://resources.wfsahq.org/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

S.C. Reale and M.K. Farber. Management of patients with suspected placenta accreta spectrum. BJA Education, 22(2): 43e51 (2022). https://www.bjaed.org/article/S2058-5349(21)00131-1/fulltext

B.D. Einerson & C.F. Weiniger. Placenta accreta spectrum disorder: updates on anesthetic and surgical

management strategies. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2021.102975

Bartels et al. Anesthesia and postpartum pain management for placenta accreta spectrum: The healthcare provider perspective. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2024;164:964–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15096

Lloyd et al. Early viscoelastometric guided fibrinogen replacement combined with escalation of clinical care reduces progression in postpartum haemorrhage: a comparison of outcomes from two prospective observational studies. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 59 (2024) 104209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2024.104209

Winearls J et al. Fibrinogen Early In Severe Trauma studY (FEISTY): results from an Australian multicentre randomised controlled pilot trial Crit Care Resusc 2021; 23(1):32 – 46. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10692540/

Carroll & Young. Intraoperative Cell Salvage. BJA Education, 21(3): 95e101 (2021). https://www.bjaed.org/article/S2058-5349(20)30157-8/fulltext

Kowalczyk et al. Fibrinogen Replacement during Postpartum Hemorrhage: Comparing Plasma, Cryoprecipitate, and Fibrinogen Concentrate. Current Anesthesiology Reports (2025) 15:39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-024-00663-8

Shah, A. and Collis, R.E. (2019), Managing obstetric haemorrhage: is it time for a more personalised approach?. Anaesthesia, 74: 961-964. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14661

Abrahamyan et al. Cost-effectiveness of Fibrinogen Concentrate vs Cryoprecipitate for Treating Acquired Hypofibrinogenemia in Bleeding Adult Cardiac Surgical Patients. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(3):245-253. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.6818

ESRA Prospect Recommendations. Pre-/Intra-operative (After Delivery) Interventions: Local and regional analgesic techniques. Caesarean Section 2020. https://esraeurope.org/prospect/procedures/caesarean-section-2020/pre-intra-operative-delivery-interventions/